Centerfolds and Center Court: The Danny McGibbeny Story

Photo by Image courtesy of Point Park University Archives

Sports Information Department: (Left to Right) Mike Taylor, Dan McGibbeny (SID) John Zingaro, Malette Poole (Assistant SID)

October 10, 2017

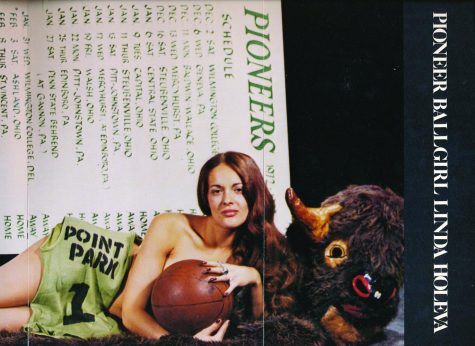

Danny Patrick McGibbeny’s first home run in life began at Point Park: running a centerfold in the 1972-73 basketball media guide depicting a scantily-clad woman that later earned mention in Sports Illustrated.

A 1973 journalism and communications graduate, this “stunt,” as local publications called it, allowed McGibbeny to quickly rise through the ranks of Pittsburgh sports before he lost his battle to cancer at the age of 26.

Shortly after his passing, his hometown of Brookline honored his memory by naming a baseball field after him and declaring Oct. 8, 1977 “Danny McGibbeny Day.” This month marks that 40-year anniversary of “The Gibber.”

From the first inning of his game, Daniel Patrick McGibbeny grew up surrounded by sports. His nephew, Clint Burton, who graduated from Point Park College’s 1983 computer science program, recalls his childhood playing everything from little league baseball to neighborhood football to basketball.

McGibbeny and Burton also enjoyed their relation to Daniel James McGibbeny, the executive sports editor at the Pittsburgh Post-Gazette during that time.

“I’d have to say that Danny, as well as myself, we lived rather privileged lives having a grandfather that could get us access to all of the Steeler games and all the Pirate games and all the Penguin games,” Burton said.

McGibbeny would later seem to follow in his father’s footsteps by pursuing a journalism career at Robert Morris Junior College. He began as the two-year college’s student sports publicist and sports editor for the newspaper.

Upon switching teams and entering Point Park College as a junior transfer in 1971, McGibbeny got involved with the Sports Information Department through a work study introduced to him by his former high school basketball coach, Jerry Conboy. At the time, Conboy was coaching the college’s basketball program, which was still in its infancy.

According to a 1972 article in the Globe, McGibbeny served that year as a general staff member in the department, which was only in its first year.

An earlier article in the Globe described the department as “a channel between the Pioneer teams and the media. Its members keep statistics at the games and send stories on the players back to hometown newspapers for exposure and recruiting purposes.”

In the fall of 1972, McGibbeny was up to bat as the department’s sports information director.

THE CENTERFOLD STUNT

Jimmy Young, then a journalism and communications freshman and fellow member in the department, recalls McGibbeny treating his new position “like a full-time job.”

“Danny treated us like way more than a small 1,100-people commuter school,” Young said. “He had a much greater vision than what it really was.”

In October of that year, that vision was focused on the college’s basketball team, which was struggling to make a name for itself in a city saturated with sports.

McGibbeny said in the Globe around that time that “the group has ‘decided to fill the Pitt Field House for home games, no matter how it’s done.’”

The sports information director was primarily responsible for compiling and editing the basketball media guide each year, which contained team profiles and statistics to aid local press while covering the Pioneers.

The pitch was a fastball right down the middle. The “centerfold stunt” appeared in the 1972-73 basketball media guide where “about 1,500 copies…[would] be printed and distributed to local press, future recruits, the NAIA and NCAA, every college in the district and news outlets for opposing teams,” according to a November 1972 Globe.

Danny McGibbeny is credited with the original idea to include a centerfold, pictured above, in the 1972-73 basketball media guide.

Young summarized the unanimous reaction to the stunt: “We got a lot of publicity out of it.”

Burton, still a young kid upon the media guide release, agreed that it went over great, although he had not learned more until years later.

Even Conboy remembered it when Burton came to Point Park, telling him, “no more centerfolds.”

Conboy revealed that “one of Danny’s toughest jobs was trying to convince him that there should be a centerfold in the sports information pamphlet,” according to a 1979 issue of the Pioneer.

In the spring of 1973, while the basketball team was having a “tremendous year” as described by the Pioneer, word of the media guide and its centerfold got sent through a local connection to Sports Illustrated.

The magazine did not publish the centerfold itself, however a “short take” mention was all McGibbeny needed to put the Pioneers on the map and garner “nationwide attention.”

LIFE AFTER POINT PARK

McGibbeny went on to graduate in the spring of 1973, the same year that the city’s World Team Tennis franchise, the Pittsburgh Triangles, made its debut.

Immediately after graduation, he took a job as the team’s publicity director where he continued to assemble media guides (sans centerfolds) and handle the press. The job also granted McGibbeny the opportunity to network with top-level names in tennis and Pittsburgh sports, which led him to befriend one of the Triangles’ owners, Frank Fuhrer.

At the same time, the McGibbenys and the Burtons were building a franchise of their own.

“Everyone in the family had a job [with the Triangles],” Burton said. “Dad did scoreboard, sisters were the ballgirls, I was a statistician…it seemed like everybody Danny knew had a job doing something.”

By 1975, it was home run after home run. McGibbeny became the team’s assistant general manager, and the Triangles won a World Team Tennis title, the King Trophy.

He met and worked with top players in the sport like Vitas Gerulaitis and Billie Jean King. He continued to be the “heart and soul of the management aspect of the team,” according to Burton. And he hadn’t forgotten about his Point Park roots.

Pete Zapadka, a journalism and communications major who graduated in December of 1974 needed an internship. He joined both the Triangles and the McGibbeny franchise as a statistician. He originally met McGibbeny around 1972 while they were students together.

“Knowing Danny helped me work out my life,” Zapadka said. “I got to meet great people and great tennis players. I got to do so many things because of Danny’s inclusiveness.”

Just kicking off his third year with the Triangles in 1976, McGibbeny had his thumb on the pulse of a championship team, but they weren’t doing well.

The team’s record was 9-18, and Mark Cox was feeling the strain of taking on the roles of both coach and player. Cox resigned, and the position went to a man who had never played tennis a day in his life.

“He had such a good relationship with the players themselves, [Fuhrer] figured that by taking the responsibility off of Mark Cox…he would lighten up,” Burton said.

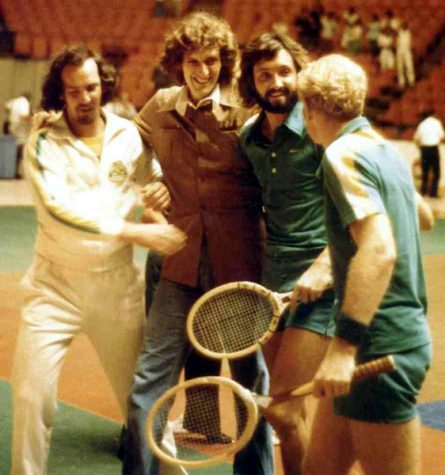

Triangles Coach Danny McGibbeny, with trainer Paul Denny

and players Bernie Mitton and Mark Cox after a match.

Under McGibbeny’s lead, the Triangles went on a nine-match winning streak, according to a 1977 article in the Pittsburgh Post-Gazette, pushing their record to 15-3 for the remainder of the season and earning a secure spot in the playoffs.

“His whole key to being the coach was the fact that he knew how to make the players feel comfortable, and just go out there and win,” Burton said. “He was their biggest cheerleader.”

The Triangles ended up losing in the World Team Tennis Eastern finals to the New York Apples. Meanwhile, Burton recalls the first signs of McGibbeny’s health declining.

MISSING MEMORIAL

In 1977, players began to leave, resulting in the Triangles folding as a team. The Pittsburgh Post-Gazette mentions McGibbeny becoming general manager over the merged Pittsburgh-Cleveland Tri-Nets, however he would resign a month later to work for Fuhrer’s credit insurance company.

Both Zapadka and Young do not recall when they found out McGibbeny was sick. Burton, a teenager by the late 70s, became close to McGibbeny while resting at home, but described his perspective as “in the dark.”

“Nobody really knew that he had lymphoma,” Burton said. “It was misdiagnosed for a while.”

On Sept. 6, 1977, after 17 days in Presbyterian University Hospital’s intensive care unit, McGibbeny passed away with his bases loaded, and his game not even half over.

On Oct. 8, friends, family and community members gathered in Brookline Park to play a softball game on the newly-named Danny McGibbeny Memorial Field.

While the game got rained out, speaker after speaker got up in Brookline’s recreation center to honor and remember “The Gibber.”

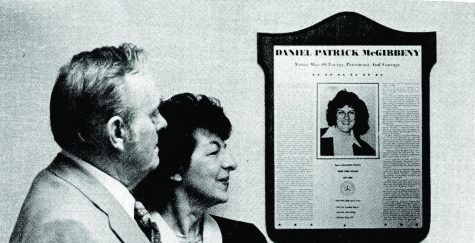

Back at Point Park, McGibbeny smiles on page two of the 1977-1978 basketball media guide. In 1979, the college placed a plaque in the sports corner of the journalism wing in the Helen-Jean Moore Library.

That plaque is currently missing.

Mr. and Mrs. Daniel McGibbeny admire the plaque placed in the Sports Corner of the Journalism Wing of the Helen-Jean Moore Library.

According to Phill Harrity, the university’s access services and archival coordinator, the exact location of the plaque is unknown.

“There was a section of the library, the journalism section of the library, that was dedicated to him,” Harrity said. “That’s when the library was located in Thayer Hall. The library moved over to [the University Center] in the 90s. They took the plaque down when they moved.”

Harrity said it’s a “matter of where it was placed when it was moved.”

Both Harrity and Burton are trying to pinpoint the plaque, which has proven to be difficult when the majority of the library staff was not around in the 90s.

FORTY YEARS UNFORGOTTEN

While the grass needs cut and home plate needs dusted off, Zapadka hit an RBI for “The Gibber” more than three decades after his death.

In 2014, Kevin Taylor, director of athletic communications, received a nomination form from Pete Zapadka to induct McGibbeny into the Pioneer Athletic Hall of Fame.

“I know he didn’t play sports [for the university,] but what he did and the notoriety he brought to the university, he should be in the Hall of Fame,” Zapadka said.

McGibbeny remains a nominee for Point Park. Even only six years after his death, he was elected into the 1983 Western Pennsylvania Sports Hall of Fame, but again, never inducted.

The accolades and dedications surrounding McGibbeny long after his time, which extend further than the aforementioned, led Burton to wonder what could have been.

“We think about things in our life that change because of this path or this path…we can all start that crossroads thing with the day that he passed away,” Burton said. “I don’t think Danny would’ve stayed in the management business, I think he would’ve become like Jerry Maguire… he would’ve been that guy making the big deals with the big players.”

From 1971 up until the summer before his death, McGibbeny still found time to coach a community little league team, where he likely got to do more coaching than he did with professional tennis players.

“I’d have to say that he was like my idol,” Burton said. “I cherished any time I got to spend with him because he was always on the move…and the kids on the team remember him with the same adulation.”

Zapadka left the Triangles while it was still under McGibbeny’s lead. He then spent more than 40 years on staff at the Pittsburgh Post-Gazette, all because McGibbeny’s father put in a good word for him.

“He was just an attractive person; he drew people in,” Zapadka said. “He certainly touched my life in ways most people have not.”

Young never graduated from Point Park. Instead he took the opportunity to work full-time at the Pittsburgh Post-Gazette as well.

“He really helped out his fellow students,” Young said. “I thought he was really ahead of his time, much more skilled. Kind of like overqualified.”

McGibbeny never made it to the ninth inning, but he still won the game, not just for himself, but for his team.

“That’s the way he was,” Burton said. “He never forgot his friends, which is why in all these years they never forgot him.”

Clint Burton • Oct 18, 2017 at 4:58 PM

Many thanks to Nicole for a great article on my Uncle Danny. It brought back so many memories and also brought me to tears (of happiness). Also great to read the comments from my old friends Coach Conboy and Pete Zapadka. The Pioneer spirit still lives in all of us!