Commonly banned book ‘Slaughterhouse-Five’ touches on anti-war themes, alien society and effects of PTSD

October 16, 2019

Language has the ability to transcend time, articulating the events of history and the lasting effects those events possess. Books are the keepers of language, passing on the words of past generations to guide the future — to point us in the right direction. So, when these books get banned from certain parts of the world, areas of the country and even schools, we are taking out an important piece of our history.

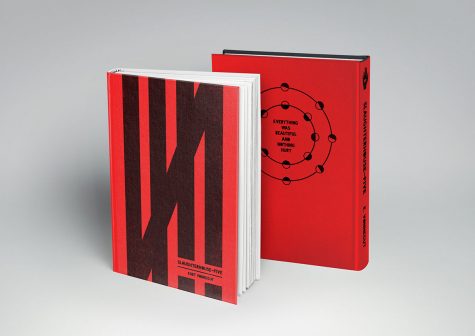

Kurt Vonnegut’s novel, “Slaughterhouse-Five,” is a perfect example of this, ranking 29th on the American Library Association’s list of banned or challenged classics. The novel follows the story of Billy Pilgrim as he suffers the effects of PTSD from World War II. He travels through his life in non-chronological order, gets kidnapped by the Tralfamadorian alien race and gives us a painful rendition of the Dresden bombings. Vonnegut knocks down the rigid structures of science and physics with his skewed version of time and forces the reader to ponder the absurdity of war in a country where there always seems to be one.

Down to its core, “Slaughterhouse-Five” is an anti-war novel. The alternate title “The Children’s Crusade: A Duty-Dance with Death” gives us more insight into the novel’s purpose; the Children’s Crusade was a real event that took place where children went to join the Crusades in Jerusalem, but many of them turned back and died before they even arrived. The pointless loss of life is a major theme in “Slaughterhouse-Five” and stems from the reality that people who fought in past wars didn’t fully understand what they were dying for, thus making them as ignorant as children.

Apparently, some didn’t like this very much and banned the book for its violence and realistic depictions. “The Atlantic” wrote that it was banned or challenged at least 18 times and the Drake Public School Board in North Dakota burned 32 copies of it in the 70s. Some called the novel anti-Christian and condemned it for its vulgar language, saying that it possessed too much sexual content. The last recorded ban of the book was in 2010 in Michigan.

The books that force us to think about the way we live are the ones that we must hold on to. Without these major pieces of history we will continue to make the same mistakes, and that’s essentially what Vonnegut wanted to tell us with his work. We see the repeating of history even when the book was being set on fire, a hapless parallel to the city of Dresden drowning in flames about 30 years earlier.

Overall, the reason this book rubs people the wrong way is because it doesn’t leave out the shocking features of America’s history that some strive to forget about. Vonnegut writes that “there is nothing intelligent to say about a massacre. Everybody is supposed to be dead, to never say anything or want anything ever again.” Our country has participated in its fair share of massacres, but we fail to see the absurdity in the forms of war that the world has brought to life.

“Slaughterhouse-Five” pushes us to question our values and illustrates the everlasting effects on the victims of war. We must push for important novels like this to be read before we continue to repeat the mistakes of the past. If we fail to do so, history, as Robert Penn Warren once wrote, will “drip in darkness like a leaking pipe in the cellar.” And so it goes.