Student loan debt: A never ending cycle

January 8, 2019

Graduate student Dani McSweeney does not pay a dime as she attends Point Park University to receive her master’s degree. However, a mound of student loan debt still awaits her from the loans she used while working toward her undergraduate degree.

Alum Lauren Ortego’s parents told her to not worry about the cost of an education when looking at universities. As her first student loan payment appeared last month, she questions if she would have considered pursuing higher education in the first place.

No two students at Point Park have the same financial situation, but 97-98% of the student population receive some type of financial aid, according to Director of Financial Aid George Santucci. Although the university attempts to help every student financially, every student will accumulate some amount of student loan debt.

“It is kind of sickening the debt you put yourself in just trying to get a four-year degree,” McSweeney said.

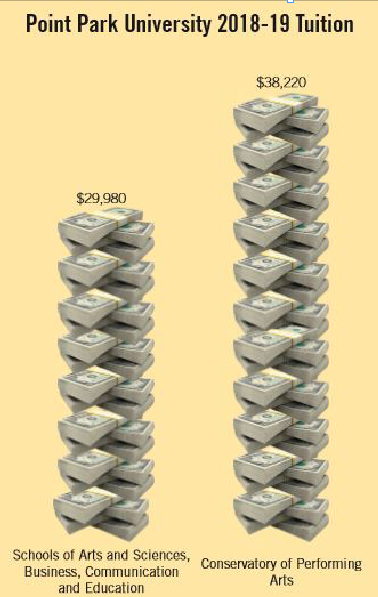

For a four-year undergraduate degree at Point Park University, the 2018-19 yearly costs are $29,980 for the Schools of Arts and Sciences, Business, Communication and Education and $38,220 for the Conservatory of Performing Arts (COPA).

Point Park University students received more than $95 million in financial aid during the 2016-17 academic year, and the average student from the class of 2017 owes nearly $20,000 in federal student loan debt. Many students utilize various types of financial aid and recognize the $1 trillion student loan debt crisis will include them in the near future.

In fact, student loan debt has climbed past $1 trillion in recent years, according to Salem Press Encyclopedia. In 2014, total student loan debt increased by $31 billion to reach $1.1 trillion. The trend continued as the total debt climbed to $1.4 trillion in 2017.

According to the article, Managing Student Loans in a Changing Landscape, by Adam S. Minsky, J.D. one of the nation’s leading experts on student debt, student loan debt is the second largest type of consumer debt. This leads students to look for various types of aid as well as resources other than loans to earn money.

Financial Aid at Point Park

Santucci said the first thing students need to complete for financial aid consideration is their Free Application for Federal Student Aid (FAFSA).

“We can’t do anything until you fill out your FAFSA,” Santucci said.

Students could begin filling out their FAFSA as early as Oct. 1, 2018, for the upcoming academic year, and it is due on May 1, 2019.

The FAFSA will inform the Financial Aid Office if a student qualifies for the Federal Pell Grant, and, if the student is a Pennsylvania resident. The FAFSA also determines if a student can receive the Pa. State Grant. Grants are money awarded that do not need to be paid back.

For the current academic year, the maximum award for full-time students for the Federal Pell Grant is $6,095, and the maximum for the Pa. State Grant is $4,122.

After the FAFSA is filled out, students have a number of options for additional financial aid. The Admissions Department determines a student’s eligibility for the university’s scholarships, and Point Park’s website dedicates pages to explain the scholarships offered by the university for various departments.

New scholarship amounts have surfaced for the 2019-2020 academic year. Every freshmen receives some type of award based on academic performance or an audition in COPA, according to Santucci.

The academic scholarships awarded to incoming students stay with the student until they graduate.

The university website also details private scholarships students can apply for if Point Park does not meet the financial need of students.

Ortego believes she received a decent amount of aid despite the high cost for a private university.

“I’m not sure if [the cost is] Point Park’s fault or the fault of education costs in the country or the government or what, but I think I got pretty lucky with the aid I received both through the school and otherwise,” Ortego said.

Following the FAFSA and university-awarded scholarships, additional money is limited, according to Santucci.

Federal student loans are capped at a maximum for every year a student is in school. The maximum is $5,500 for freshmen, $6,500 for sophomores and $7,500 for juniors and seniors.

“For each level that you’re here, there’s a maximum that I can award you,” Santucci said. “I cannot go over that maximum, and that’s a way that they tried to keep the loan debt down, by not allowing a student to come in and just capitalize or say ‘I need $10,000 every year.’”

If that amount is not enough for the cost of education, the student’s parent can go through an approval process for a Parent Plus Loan based on the parent’s income. The maximums for this loan are significantly higher and can even total the remaining amount of the cost of education.

If the parent is not approved for the Parent Plus Loan, a student can borrow an extra $4,000 in an unsubsidized loan, which accrues interest while a student attends school.

Unsubsidized loans can put a student in more debt than they originally planned due to the accumulating interest.

“In the end, I’ll be paying over $100,000 back,” Ortego said. “My loans added up are only around $40,000. Isn’t that insane?”

After federal loans, private alternative loans from local lenders such as local banks become an option.

Work study remains another option for students who qualify. However, the student directly receives the money rather than subtracting the amount from existing tuition.

An option that the university does not publicly advertise is filing a financial appeal. When a dramatic financial shift occurs within a student’s family, a student can request more money through Point Park’s Appeals Fund.

The FAFSA uses information from two years prior, and a lot can change in two years, according to Santucci. A family can experience a financial shift due to unemployment, loss of a family member, etc.

“Give us the paperwork,” Santucci said. “Give us the numbers. We’ll use those numbers to see if you qualify, but it’s not necessarily that you’re going to qualify.”

The student can explain their situation and provide the necessary paperwork to a financial aid counselor, and the next step will be to alter the FAFSA to see if the student qualifies for the state grant or the Federal Pell Grant. Then, the appeal will be taken to a university committee to see if the student can be helped with endowment funds.

Students and their families have numerous concerns when it comes to their finances.

According to Santucci, families who believe they should qualify for certain aid believe it is the university denying them when it’s really the federal government.

Students also confuse their Expected Family Contribution (EFC) with the amount they actually owe for their education. The EFC is based on the family’s income and tells the university how much a student may be assisted by their family.

Families with a lower income with social security benefits, a death in the family or single-parent families will have a 0 EFC. The cost of education minus the EFC is the financial need of the student.

The most concerning aspect of all is the actual cost of pursuing higher education.

Coins and Concerns

McSweeney graduated with a bachelor’s degree in sports, arts and entertainment management (SAEM) in Dec. 2017. She now serves part-time as the Graduate Assistant for The Pittsburgh Center for Sports Media and Marketing and also holds a full-time position with the Pittsburgh Penguins.

“For as long as I have been in school, I was always told I ‘wasn’t going to make great money’ in the sports industry,” McSweeney said. “Now that I have a full time job, I see that very clearly.”

She currently makes small payments on her undergraduate student loans when she is capable, but McSweeney is preparing to make changes in her daily life once she graduates.

“I think in order to ‘live comfortable’ while also paying my loans, I am going to have to cut back on a lot of things,” McSweeney said. “I already pay rent, a car payment, utilities and much more and the thought of having another $400 bill on top of that really makes a person nervous, especially when they are making less than $30,000 per year. Hopefully with a master’s degree this helps my income level, but it’s just not guaranteed.”

Ortego relates to McSweeney’s lifestyle change all too well.

“My game plan includes shopping exclusively at Aldi where everything is way cheaper, not buying as many clothes as I always have, unless there’s a really good sale, and not eating out as much, which is a habit I picked up in college,” Ortego said.

The two have a solid grasp on what they need to accomplish to keep up with student loan payments. However, inserting a student loan payment is easier said than done. Not every student displays preparedness like McSweeney and Ortego.

Senior mass communications student Sara Flanders acquired a transfer student scholarship and university grant upon coming to Point Park, but she worries about paying off her loans as her graduation date approaches.

“Just looking at job postings now is showing me that a lot of entry level jobs require a lot but don’t have great pay,” Flanders said “I was hoping to have more money in my savings for a buffer when I graduate, but I can only work so much with school so all of my paycheck goes to everyday expenses.”

Flanders hopes to make enough money after graduation to pay more than needed every month but admits to not having much more of a plan.

Senior broadcast reporting student Nicholas Brlansky currently pays interest from time to time, although it is not a typical practice among students, according to Santucci.

“Repay on your loans while you can,” Santucci said. “It could go to food and entertainment. Try and make the payments if you can.”

With graduation looming around the corner, Brlansky hopes for the same as Sayers and Flanders: make enough money to make loan payments.

“My general plan for now is to save a portion of my income from now until the six-month deferment is up to have a small savings for just paying off student loans,” Brlansky said. “After that I plan on inserting my loan payment into my budget.”

With so much blind hope and general plans, sophomore SAEM student Bryana Appley said it most candid when she said, “We can never really know [about our future] until it comes time.”

Appley was the first of her family to attend college, so the unknown has existed since day one. After a stressful first semester, financial advisors directed her family down a path that would work for them.

Appley’s parents help with daily necessities and other miscellaneous items, but she creates her own income working at Heinz Field and booking paid gigs to further her career in the music industry.

“Some days I am super confident in my abilities and my networking connections, and other days I just take in the difficulty of everything and realize that life isn’t always that simple,” Appley said.

The aspiring musician is only in her second year of undergrad, and like Flanders and Brlanksy, Appley hopes for a steady job to repay loans after graduation. Just as Appley stepped into the unknown of her first day, the unknown remains with every student until their first student loan bill arrives in the mailbox.

For some, that was last month.

The Corner of Real and World

76% of Point Park’s 2017 graduating class borrowed student loans. The average student from the 2017 class graduated with $19,326 in federal student loan debt. With the addition of private loans, the average debt climbed to $27,924, according to US News.

Federal student loans and private loans are deferred for six months after a student graduates from Point Park. Then, a student has 10 years to repay the loans.

The federal government bases the payment plan on the amount the student borrowed. For example, if a student accumulated four years-worth of federal student loans, the total would be $27,000. Santucci said the monthly payment for that amount of debt would be roughly $270 per month for 10 years.

Appley, Brlansky and Flanders know repayment is awaiting months down the road but don’t have much of a game plan yet. McSweeney recognizes the numbers she will soon have to work into her budget but also doesn’t need to fret immediately.

For recent graduates, repayment has now become a reality.

Ortego, a mass communication graduate, owed her first student loan payment on Dec. 16. Her payment will remain around $350 per month for the time being.

“I opted for a plan that will increase the payments as I get older because I will, assumedly, be getting better jobs and higher paychecks,” Ortego said. “We’ll see how that works out.”

Ortego’s loans only added up to roughly $40,000, but the recent graduate said the interest is the most difficult aspect of paying back her loans. She said the end result will result in about $100,000-worth of student loan debt.

“The payment plan is for 300 months, which is 25 years,” Ortego said. “I’ll be in my late 40s when I make my final payment.”

Currently, Ortego earns money through three part-time jobs. Ortego works as a content creator and editor at Flying Cork, a digital marketing firm, a customer service representative at Giant Eagle and a freelance contributor for different publications, including the Pittsburgh City Paper and the Pittsburgh Current. This month, she will begin her first full-time position.

Ortego claimed to be confident in her financial situation until about a month prior to her first payment.

“Then I started setting up payment plans and consolidating my loans and I even downloaded the Federal Loan app so I can see them all in one place,” Ortego said. “That’s when it set in that I may not do as well as I thought I would, despite having three-ish jobs. I’ll basically be paying my rent twice.”

2018 broadcast reporting graduate Josh Croup experiences a similar reality as his repayment date approached in mid-December as well.

When Croup attended Point Park, the Vice-Presidential scholarship covered a “good chunk” of his tuition. Grants and loans lessened the cost, and Croup opted to pay the remaining balance out of pocket.

“I’ll never forget the gut-wrenching feeling of writing a four-figure check,” Croup said.

His new payment may not be four figures, but it will take a significant amount of his paycheck.

“My job doesn’t pay a lot,” Croup said. “I at least had some spending money left over after my paychecks went toward living expenses. When December comes, that money all will go toward my student loan payments.”

Croup works as a morning anchor at WDTV in Bridgeport, W.VA. While he now shifts his leisure money into student loan payments, Croup also has a savings account to use in times of trouble and a support system to lean on in financial crises.

“I’m the first in my immediate family to go to college, so it’s a learning experience for us all,” Croup said. “We had no idea what we were getting into when I took out loans. Luckily, it looks like I’m not going to be as buried as I initially thought in student debt.”

Students who may not be totally buried alive in student loan debt will be crawling, slowly but surely, out of the debt grave until the balance rings zero – years from now.

Ortego’s father remains in debt and helps his daughter when he can.

“Now, he and my mom have to help out my sister and I with [our loans],” Ortego said. “It’s crazy how cyclical student loans are. Just when you finish yours, now it’s time for your kid to go off and get their own. It’s never-ending.”